It was a milestone moment in open government in 1968 when then California Gov. Ronald Reagan signed into law what was intended to give all citizens a legal right to inspect and get copies of government records.

It was followed by Proposition 59 In 2004, when voters overwhelmingly approved adding the right of access to government records to the California Constitution. This applies to more than 5,500 state and local government entities, from cities and water districts to police and sheriff’s departments.

More than 50 years after that first piece of legislation, open records advocates say the California Public Records Act is not delivering on the promise of transparency in government.

One leading advocate is attorney Jerry Flanagan of Consumer Watchdog, who said that the CPRA has “more holes than non-holes — it’s like a piece of Swiss cheese.”

To remedy the problem, a 2024 voter initiative is being created to plug some of those holes, like long delays in providing information or agencies hiding behind claims they are exempt from giving up the information and records.

The truth is, say some experts, the CPRA’s problems began at birth. It was not fully developed when it was delivered by the state Legislature to the public. This defect allowed the same legislators who signed off on the bill to excuse themselves from having to comply.

Flanagan said the legislature exempted itself from the Public Records Act, and created another piece of legislation in 1975 called the Legislative Open Records Act that has even more loopholes. The proposed ballot measure would address loopholes in both laws.”

Flanagan is joined by Public Records Act litigator Kelly Aviles in creating a ballot measure for 2024. Both have expertise from years of wrestling matches with agencies across the state.

David Loy, legal director for the First Amendment Coalition, is one of the lawyers who goes to state courts to try to unlock those public records. His job is to advocate for the public’s right to know. Loy said agencies are often guilty of foot-dragging, noting that it’s “a chronic problem that we hear about.”

“The reasons for delays are as varied as the requests being made to find out information citizens are entitled to,” he said.

There are no penalties or sanctions for non-compliance. Loy said the only consequences are that “if the agency is sued, they might have to produce the records, if ordered by a court, and might have to pay the plaintiff’s attorney bill.”

What happens when agencies “dig in”? Flanagan cited as an example the legal battle with the California Public Utilities Commission over its resistance to disclose records that would eventually reveal how Pacific Gas and Electric tried to conceal operational flaws that led to the wildfire that destroyed the town of Paradise in 2018.

Like many journalists in San Diego County, Miriam Raftery, editor of East County Magazine, has had numerous run-ins over public records. She’s been “stonewalled on records,” she said, like when she requested information about “Cajon Valley’s lavish expenditures on retreats for school board members, national/international travel costs of a superintendent, etc.” In this case and others, she said, “records have often been late, partial, or not turned over at all.”

Ken Stone, contributing editor at Times of San Diego, requested documents from the city of Escondido after Rep. Darrel Issa held a forum on the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan including Gold Star families at city hall. They were relatives of service personnel killed at the Kabul airport.

This was clearly a topic of public interest, and Stone was researching how the forum came about. For example, did the congressman pay for the use of the city chambers? “Escondido shared minimal public documents and little email correspondence,” said Stone. He added that “about 20 messages came in “msg” format, which I couldn’t open no matter how hard I tried.”

San Diego attorney Cory Briggs is active in litigation over CPRA issues. He provided a current example of extensive “stonewalling,” saying his client, Project for Open Government, is currently suing the city of San Diego over the many requests made to the city that are still pending.

“It has hundreds of outstanding requests that are more than a year old,” he said.

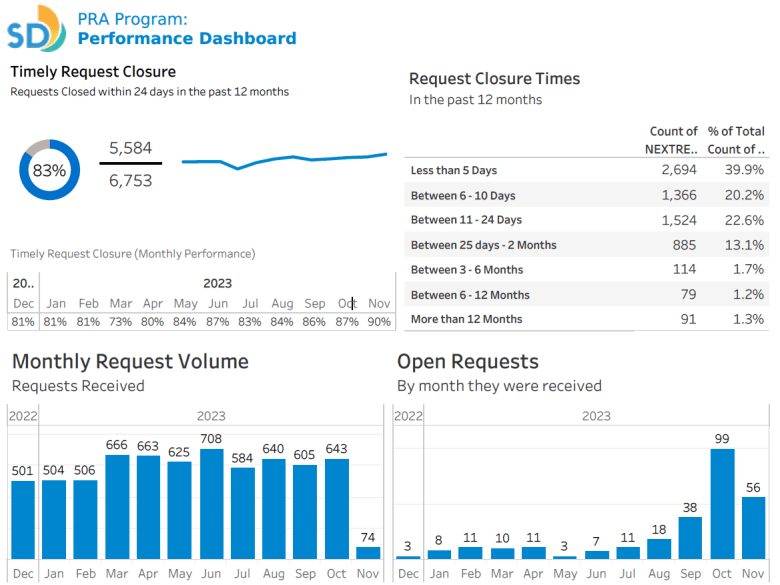

His lawsuit notes that as of November of last year, the city “had more than 4,000 incomplete requests for public records on the NextRequest platform” that had been open for more than 30 days — going back to Jan. 1, 2018. NextRequest is the system the city uses to handle open records requests.

“The city is fighting tooth and nail,” Briggs said.

City Attorney Mara Elliott’s office says it complies as quickly as it can to requests, and each request is answered in the order it was received. However, the City Attorney herself acknowledges that more effort is needed to increase transparency in San Diego City Government.

The city currently has 476 open requests, and reports consistently closing more than 80% of PRA requests within 24 days. So far this year, the city has received more than 6,300 requests.

Elliott pointed out that her office “has long advocated for the creation of an Office of Transparency to expedite the review and production of requested city records.” Coming soon, she said, is a transparency measure for lobbying, campaign contributions, and conflicts of interest. It would also “prohibit the use of personal devices for city business.”

Loy added that not all agencies in California are misbehaving or not complying with the spirit of the open records act. But many do have a common complaint, that they are very busy. They will argue they have other more pressing matters to take care of and other public service issues to be handled.

But Loy is not buying it. He said CPRA requests “should not be an afterthought, or a secondary public service. It is every bit as critical a public service as other public services like police, fire, water, sewer because transparency is the oxygen of accountability.”

Government entities often ignore another element of the existing law — if they can’t provide the requested information they need to make an effort to help provide where the information can be obtained.

As someone who has filed hundreds of requests over the years, I can say this help rarely, if ever, is offered.

“They don’t try to actually find documents, they don’t ask questions, they limit their search dramatically,” Flanagan said. “And that’s really a great way not to produce documents, you just don’t look for them, so you’ve got nothing to produce.”

I currently have an open records request with the San Diego County Regional Airport Authority filed in the spring of this year. It was for “all communications regarding the installation of face recognition technology at San Diego International.” I wanted to know who got the contract and why.

I added, “I don’t expect information that would hinder security efforts but I do hope to receive detailed information on whose product is being used.” Every month since the May filing the agency sends me an email saying it needs more time. Just recently I offered to reframe my request and asked if the agency was interested in talking. The goal was to speed up the process. I never received a response.

“It is their duty to cooperate with requesters. You went above and beyond by offering to negotiate and cooperate,” Loy said. “They should work with requesters to overcome practical obstacles to make compliance more efficient.”

I recently reconnected with the Airport Authority and notified the agency that I was referencing my request to the authority as part of my story. While not acknowledging that it should have taken me up on my offer the first time, Airport Authority spokeswoman Nicole Hall told me, “This may be a way for us to get you the records and information you seek on a more expedited basis. We are glad to work with you to accomplish that.” She also said the person handling the request was out of the office, so I would have to wait until she returns.

The 5,500 California state and local agencies might reconsider how they treat CPRA requests with or without a new ballot measure. The federal government has its own open records act system and recently analyzed Freedom of Information requests to the Department of Health and Human Services between 2008 and 2017.

Flanagan said the recommendations could well apply to California agencies. Those findings suggested that HHS and the FDA “might be made more efficient through greater proactive record disclosure.”

It concluded that, “given growing costs, minimal fees collected, and sometimes lengthy process times,” the HHS should consider expanding efforts to proactively disclose records. “These efforts might both improve agency transparency” and make the information programs more efficient.