Robert Rohrbach was on a Hell Week run with fellow SEAL candidates when the urge to quit hit. A nearby comrade pulled him into the middle. Now two buddies were holding him up.

The moment passed and so did his impulse to drop out.

It’s called the 30-second period, he says — when you reach the point of giving in, if you just keep putting one foot in front of the other, time disappears and you forget that you thought you couldn’t make it.

At least that’s how 80-year-old Rohrback remembers it. One of the two helpers dismisses the story.

Was it a hallucination amid sleep deprivation? Rohrbach isn’t sure.

Famously secretive about their missions, retired SEALs on last weekend’s Honor Flight San Diego journey to Washington confided how they survived intense training and what the public gets wrong about their warrior brotherhood.

Their mystique.

Rohrbach was part of a 90-member Navy Special Warfare Operator group on the three-day journey, several of whom reflected on what it means to be a SEAL. These included Frogmen, Underwater Demolition Team members and Boatsmen.

“We are not big hairy monsters,” the retired SEAL said when asked the biggest misconception about his cohort — some who served in the elite group’s first decade (SEAL teams were developed in 1962).

“We’re ordinary people,” he said. “Most have a great sense of humor and a terrific drive.”

Twice a year, Honor Flight San Diego takes around 90 veterans to Washington, D.C., to visit war memorials that honor their service in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

Among those on the journey were Medal of Honor recipient Lt. Mike Thornton and Walter “Ditti” Dittmar, force master chief of Navy Special Warfare Command. Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro met the San Diego contingent at the FDR Memorial.

But it’s the renewed connections and quality time with former comrades that has proven to be a huge part of the trips’ meaningful — even lifesaving — nature. Plus the enthusiastic homecoming at journey’s end.

In April, it was Naval Special Warfare members — “the men with green faces,” the “silent ones” — to be recognized.

“That we’re all big, brawny bad guys” was retired SEAL Gene Peterson’s response to the misconception question.

“I’m a little puny guy,” said Peterson, 76. “I was only 150 pounds when I went in. I wasn’t some great big brute, but I was able to carry the boat and stuff because my head didn’t hardly touch the boat and the big guys had to carry it.”

Peterson went on to spend 30 years as a Los Angeles Police Department officer.

‘One of the Nicest Guys’

Retired warfare operator Andy McTigue’s reply to the misconception question: “That we’re all killers, and were killers after the fact — and we’re not.”

“I’m one of the nicest guys that you’ll ever meet,” he said, adding that he has been compared to Mr. Rogers.

All of the military men on the trip back East, except for an 89-year-old Korean War era operator, served one or numerous Vietnam combat tours of six months each. Comrades remarked at a dinner presentation in Baltimore that that generation of warriors is considered by counterparts to be the strong initial foundation of the force.

Some told of hours-long firefights and seeing others in their unit die. Others spoke of their reconnaissance and engineering tasks. Many stories were shared only among themselves.

Some in wheelchairs had visible reminders of their willingness to fight oversees. Others gave hints about past animosities or internal battles. (At Arlington’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, one SEAL was heard saying: “I have scars, but these days I have so many wrinkles, they cover them up.”)

Those interviewed expressed pride without regret for their arduous, dangerous work in Southeast Asia. They had satisfaction that they followed their training and completed their missions. And used that knowledge throughout their lives.

“The stuff that I’ve done, the places I’ve gone — just unbelievable,” said retired SEAL Allan Starr of Redmond, Oregon. “We go where we’re told to go, and what your goals are, and what you’re able to do. So I just loved it.”

Was it hard on my family? he asked and answered.

“Yes, when the phone rang you maybe have 30 minutes … to be at work,” Starr said. “And you can’t tell … where you’re going, what you’re going to do, when you’re coming back.”

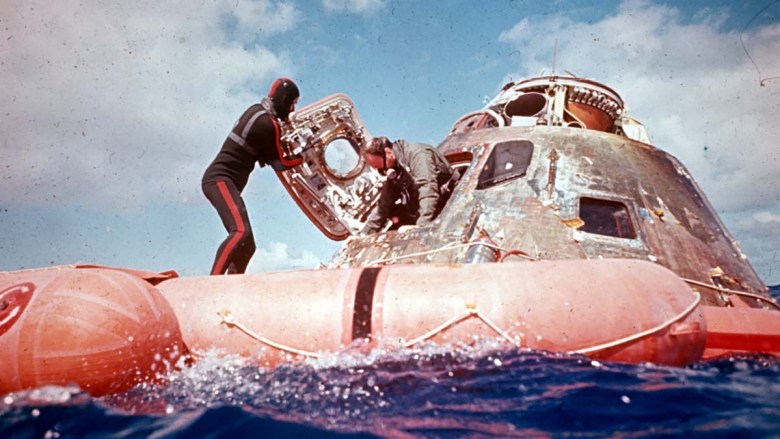

Rohrbach’s skills put him in the spotlight when he helped retrieve Apollo 11 and 14 astronauts after splashdown. For Apollo 11 — the first moon landing — he wore a special face mask with filter to protect against possible “moon germs.”

For Apollo 14, he summoned the helicopter to get Alan Shepard, Edgar Mitchell and Stuart Roosa back to land.

So what’s the makeup of a SEAL? And who made it through notorious Hell Week in the 1960s and 1970s? And how? Can you look at a recruit on Day 1 and predict whether he’ll graduate?

Rohrbach thinks not.

“Some of the fastest and smartest guys couldn’t make it, and it’s not that they weren’t capable,” said Rohrbach, who was in Navy uniform until 1998.

“It’s because they really didn’t want it badly enough to bear up under the pressure,” he said. “It’s not worth it (to them).”

It’s the risk-reward equation, and some thought the extreme training wasn’t worth becoming a SEAL, he explained. “You have to be willing to put up with anything and everything in order to achieve the goal of graduating.”

The long runs, hours-long swims, sleepless nights and freezing waters are well known.

And that ordeal included mental harassment, he said. He recalled feeling devastated when he was told early on that he was the “worst person to ever go through training.”

He perked up when — after relaying the story to a fellow trainee in chow hall — the man said an instructor told him the same thing the day before.

Mental Toughness Key

All those interviewed agreed that the mental component played a larger role than the physical.

Rohrbach recalls the morning after his first day of pre-SEAL training in Coronado.

“The next morning, I couldn’t get out of bed. Every inch of my body ached,” he said. Despite that he crawled out of bed and into the shower, and returned to training.

Rohrbach had skin grafts on both ankles following a childhood accident. Those grafts opened up with the continuous rubbing of his military boots during runs. Told by medical personnel that he should just give up, he followed an unofficial suggestion to cut a hole in the back of his boots, cover the hole with a black sock and lower the hems on his pants.

That got him through SEAL training, but his bogus claim about shark bites creating the boot hole wasn’t true. Yet it got him past a curious superior.

Veteran Starr recalled that wherever troops were on the move, they ran — as a class leader sang cadence. One trainee quit after 30 minutes, he said.

“I’m going: ‘Holy crap, we haven’t even gotten started, and now this happens,” he said.

Starr watched as, one by one, candidates quit. But he just persisted, telling himself: “I’m going to get through this, I can do this, I can do this.”

But once you get through BUD/S (SEAL) training, he said, “there isn’t anything you think you can’t do. You just go and, like I said: If you break your leg, we just [apply] a couple wraps of duct tape on it and send you down the road.”

Of training, Peterson recalls: “I mean I had several times where I blacked out because of the cold. And one time I remember crawling out of the water, getting on the back of the truck and that’s the last thing I remember until I’m sitting on the bus with my gun.”

After he took a shower and got cleaned up, he went out to the range.

‘Never Quit’ Stance

“I don’t remember anything in between,” he said. “It’s the same type of attitude when you go out in combat — never quit.”

Retired Cmdr. R.J. Thomas was knocked out of a Seawolf helicopter when it was hit by enemy anti-aircraft fire over South Vietnam. Once on the ground, using the fallen pilot’s gun, he prevailed in a gunfight that avoided capture of him and others.

He was awarded the Navy Cross for his bravery.

The public thinks SEALs are “some kind of Superman,” he said, “and in a way they are, but it has very little to do with physical capabilities. It’s mostly mental. It’s having the right attitude and the ability to believe in yourself that there’s nothing that’s impossible if you put your mind to it.”

Thomas’s specialty was marksmanship — he won multiple Navy titles.

“Doesn’t matter how good a parachutist or swimmer or runner or hand-to-hand combat person you are,” he said. “If you can’t win the gunfight when you have one, it’s all for naught.”

So Thomas became a shooting trainer. He developed all SEAL Team sniper forces, close-quarter battle courses, “all of the, you know, sub-gun training — all of that stuff. I developed all of that for the SEAL team.”

And that’s what he’s most proud of.

“Half the guys sitting at this table, I taught how to shoot,” he said at a Baltimore hotel banquet hall. “There are no less than 20 SEAL Team people that I trained who are now distinguished or double-distinguished with a rifle and pistol.”

Retired SEAL Chuck Chaldekas recalled that doubts crept in during training.

“There are always questions of that sort,” he said. “On Friday nights every week. I would call home, talked to my parents. After describing things I did, my mother would say, ‘Well, I’m confident that you can make it through this training.’ And who was I to question that?”

Special warfare operators on the D.C. trip went on to be mayors, police officers, novelists, judges and businessmen.

Peterson said his training “gave me the confidence to do what I needed to do to handle the situation when I was doing the LAPD work, to approach people, talk to people be able to do stuff with them [and] understand how to work with people.”

“That gave me the confidence to understand how to work with people when they have problems,” he said.

Said David Walker, a Seabee embedded with a SEAL team: “We’re just ordinary guys that just have that grit that just won’t quit…. Focus on what you want and keep working towards it and you’ll get there.”

Walker was a police officer and chaplain in the San Jose area for 24 years.

Ground Zero Volunteer

As part of that duty, he volunteered to assist at New York City’s Ground Zero after 9/11.

“Another thing I learned — and I solidly believe this — [is] that each one of us … here today is here for a purpose,” the 77-year-old said. “And I know that there are a couple times that I should have been killed and I wasn’t.”

Walker said comrades once even thought he was dead, and worked on him for about a half-hour to revive him.

“We got hit with a rocket round, and I got through that, and the guy that was standing by (a short distance away) got killed and I survived it,” Walker said. “We’re all designed for a purpose, and we have a calling in our lives.”

Walker, who turned 19 on his first day of boot camp, said that in his team’s free time, the group built a sewer system for an orphanage. They also retrained some captured soldiers, teaching them how to maintain and operate farm machinery as well as trade skills.

Veteran Andy McTigue, whose service dog, Selkie, accompanied him to D.C, said his time in Vietnam led him to train service dogs for veterans for a living. Selkie is trained to respond to a medical emergency.

McTigue said the pairing of dog and veteran is meant to better the owner’s life and prevent service members’ suicides.

McTigue supported Department of Transportation rules prohibiting mere emotional support dogs on airlines.

Chaldekas talked about how being trained as a SEAL has benefited him: “It taught me that regardless of the problems that you see in life, if you expend a little bit of energy and stick to what you plan to do, you will succeed. You’ve been tested and tasked to do unusual things — for the general populous — but once you do those things a couple of times, it’s like any other task.

“But the confidence that you develop with those family members, brothers of yours, let you know that you can reach a little bit further down and succeed at what you are trying to do.”

Rohrbach said many things have changed since he finished BUD/S Class 49. Weapons and equipment have evolved. Elbow and knee pads are now available, he said.

Now Better Prepared

He believes new trainees are better prepared psychologically, and mental health staff is on board in addition to daily medical reviews.

Rohrbach’s sons Christopher and Ed joined him in the Navy as they went on to command SEAL teams themselves, so they’ve had the ability to compare notes on their service. Also two grandchildren have been accepted at the U.S. Naval Academy.

Son Ed was his guardian on Honor Flight. Rohrbach commissioned both sons before retiring.

Training is longer than it was for Vietnam-era vets, Rohrbach said. Whereas he and his peers had only 29 weeks plus a probationary period, today’s SEAL trainees go through a year of readiness before receiving their trident at graduation.

“Someone once told me they teach us how to do 10 times more than we think we can do,” he said. That way SEALs may find some tasks easier compared to Hell Week.

“I love the explosives and the weapons and the jumping and diving,” Rohrbach said. “It was all exciting. Every day was different. You never knew what you were going to do, or where you would be or how long a day it would be. Sometimes the days would be a couple of days, one after the other.”

SEAL training has an attrition rate of 75%-80%, according to the Navy.

The fighters learn their limits. “I know I can stay awake for three days and still function,” Rohrbach said. “I know I can swim six or seven miles.”

Then shorter distances don’t feel so daunting later.

Rohrbach wrote letters to five best friends, saying: “This is the last letter you will receive from me until I graduate.”

Whenever he felt miserable, he thought: “I don’t want to send the letter saying I quit. It gave me a feeling of can’t-let-them-down. You said you were going to do it, now you’re going to do it.”

Medal of Honor recipient Thornton spoke to the group last weekend in Baltimore.

Thornton said he wears his Medal of Honor for “all the people who didn’t come back.”

“We’ve always been there for each other,” said Thornton, who was honored for saving the life of his superior during an hours-long firefight in 1972. “We never ran. We protected each other.

“We’re a team. And I’ll tell you one thing — we’ve been in a lot of fights together in Vietnam and we stood together. We sure as hell didn’t care what the odds were in Vietnam.”