The water cooler is no longer the center of social life in the workplace. Neither is the coffee pot, the candy stash, or the bar just around the corner. In the past two years, the pandemic pushed office dialogue online, moving communications to instant messaging, email, and virtual meetings.

As work talk moved online, it also multiplied. Meetings across the board increased 70% once organizations began the switch to remote work. Eighty-five percent of those were held virtually. Meanwhile, many workers reported experiencing unpleasant feelings when sorting through the daily slog of unopened emails or instant messages. A third of white-collar workers said frustration over email was likely to push them to quit.

It’s no wonder, then, that office workers began to coin terms like “Zoom fatigue” and “email fatigue.” Researchers at Stanford attributed workers’ video-call burnout to factors such as excessive amounts of eye contact, long periods of sitting still, and a heightened cognitive load.

Despite the excess of digital communications, many workers reported a growing sense of loneliness and isolation from the beginning of the pandemic. And research has highlighted the detrimental effects of widespread remote work on communication and collaboration. As Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella told the New Yorker’s John Searook: “Digital technology should not be a substitute for human connection.”

While loneliness may have captured the conversation, the impact of lack of connection on employee learning and growth is no less important. Workplace learning had always been about something far bigger than training programs and L&D systems. That has become more obvious during the pandemic when on-demand and bite-sized learning modules haven’t satisfied employees’ needs and hunger for development and growth opportunities. The need for special consideration becomes more urgent when we bring the youngest generation of workers into the equation.

Employers must take care to plan workplace interactions in order to maximize benefits and minimize costs. It’s widely reported that workers are more invested in their jobs when employers provide new challenges and opportunities to expand their skills. But how can organizations deliver on this essential element of employee engagement when workers are already burned out by incessant virtual communication?

What the data say:

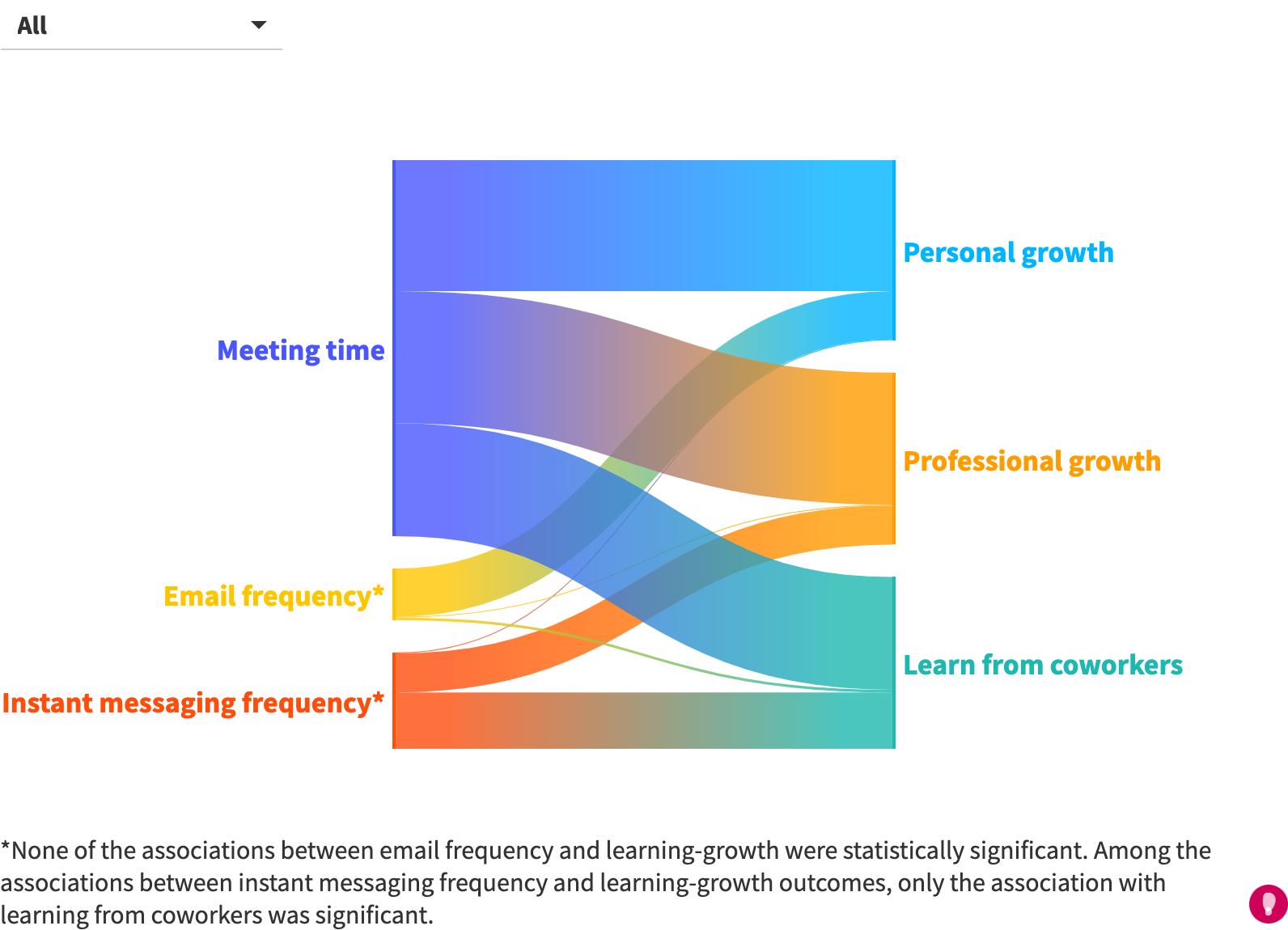

We wanted to examine the effect of workplace communications on social learning and growth, so we surveyed more than 1,000 working adults in the U.S. BetterUp’s Khoa Le Nguyen, an applied behavioral scientist, first broke communications into two groups: Synchronous interactions such as in-person, video and audio meetings, and asynchronous interactions, like email and instant messaging. He then asked respondents to rate the personal growth, professional growth and team learning they experienced with synchronous and asynchronous interactions in the last three months.

The data yielded useful insights into the connections — or lack thereof — between different types of communication and growth. First, we found that synchronous interactions like meeting time predict learning and growth better or much better than asynchronous interactions like email and instant messaging.

We also found no significant link between the quantity of asynchronous interactions and growth outcomes, except between the frequency of instant messaging and learning from co-workers. Meanwhile, all associations between synchronous interactions with growth and learning were significant.

What does it mean?

Our survey results tell us that, compared to asynchronous interactions, synchronous interactions may foster learning and growth better. This means that workers’ time spent on email and instant message platforms may do less for their personal and professional development than the hours they spend in in-person, video, or audio meetings.

We already understood the importance of social learning in the workplace. But these findings may help leaders better navigate the conundrum of telework, where remote and hybrid workers are at once deeply fatigued by virtual communications and deeply in need of human connection.

For instance, the data may help a manager decide to dedicate a portion of her team’s weekly Zoom meeting to best practice sharing, especially if that’s something the team previously did over email. Another leader deliberating over his bi-weekly one-on-ones may feel encouraged to keep going with the meetings over the phone, rather than moving them to Slack or Teams.

These findings may be especially useful to organizations keen on developing learning programs. Many employers use classroom training, experiential learning, and on-the-job skill application as learning mechanisms within the workplace. But fewer organizations have instituted formal efforts to foster peer-to-peer learning.

However employers apply these findings, we know that the conversation surrounding remote work and the health of remote workers is an important one. Somewhere between one-half and two-thirds of American employees worked virtually during the first two years of the pandemic. And despite some companies making headlines as they resume in-office operations, we know that remote work is here to stay.

That said, many workers have been unhappy with the setup. Nearly two-thirds of workers in a 2020 poll said they thought the cons of remote work out of the pros. The respondents cited unreasonable workloads, lack of connection to their team, and their company’s poor handling of the transition to remote work.

The onus is on employers to address these problems, especially if they plan to rely on remote work as their default setup or offer the arrangement as a benefit. Workers want an employee experience that invigorates them personally and professionally whether they work in an office or from the home. A key part of that experience is social interaction and growth. But employers must find the balance between connectedness and fatigue, or risk losing workers who move to employers more adept at maintaining the equilibrium.